ELITE PERFORMANCE

Overreaching and Overtraining

The overreaching training theory is a method the strength and conditioning coach implements in their training programming to produce a specific adaptation to enhance the physical qualities in athletes (Tian et al., 2014; Matos, Winsley & Williams, 2011). For rugby players, these specific adaptations are normally to increase muscle size, improve force production and to be able to repeat power outputs. For these qualities to be enhanced, an overload in training stimulus from the weights room must be applied (Bartholomew, Stults-Kolehmainen, Elrod & Todd, 2008).

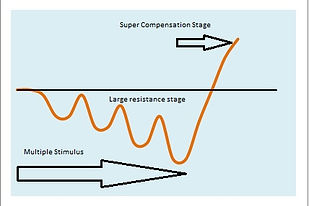

When this stimulus is applied each training session, using Dr Selye’s (1950) general adaptive syndrome (GAS) theory will show how athletes react to that mechanical stressor. When mechanical stress is applied, for a short time period after, the athlete performance decreases which is called the alarm stage. The athlete then starts to recover through the resistance stage and then compensates where performance elevates higher than the beginning baseline. This compensation effect takes place given that enough rest has been granted to the athlete before applying the next mechanical stressor where the same process happens again. Over a period of time, performance markers have gradually continued to rise above the initial baseline due to the compensation effect and performance has subsequently improved (Souza et al., 2014).

Moreover, if the weight training sessions are conducted too far apart from one another, the compensation effect window will be missed which can lead to a non-significant outcome in more advanced athletes.

However, during a three to six week preseason spell where rugby players have a certain window to get into elite condition, players will be purposely put under a large amount of mechanical stress. To force optimal adaptation, this is commonly known as functional overreaching (Halson & Jeukendrup, 2004). Using the GAS model again, it would indicate that the player would be in an ‘overtrained’ condition as the athlete will spend longer in the ‘alarm and resistance’ phase of the theory. This is due to the continuum of drop in levels from the baseline whilst not given enough rest between sessions to fully recover. However, this is designed intentionally as during the resistance phase players will adapt to the mechanical stress and improve function at a cellular level (Coutts, Reaburn, Piva & Rowsell, 2007). However, by programming a taper week to allow efficient recovery, this will generate a large increase in performance (Bishop, Jones & Woods, 2008). This is called a super compensation effect due to reaching a higher threshold compared to the earlier compensation effect.

Nevertheless, the GAS theory will look completely different if a player suffers from overtraining. The model shows a drop in performance through the alarm and resistance stage, but the compensatory stage doesn’t return to base line levels like in the overreaching model. This potentially is down to larger stressors being placed upon a player or not given enough recovery time between external stressors (Meeusen et al., 2006). This is can also be called non-functional overreaching because the player has not intentionally been placed under great amounts of stress (weeks leading into months) (Kentta & Hassmen, 1998). However, the individual is expected to make a full recovery within a few weeks of rest.

However, when not acted upon correctly, over a large period of time (up to six plus months) the athlete’s performance will continue to fall well below the existing base line. If this was to occur, it can be detrimental to the athlete in question as they would need a huge rest period. Still it won’t guarantee that athlete will recover to previous performance levels. This can be diagnosed as unexplained under performance syndrome (UUPS) (Budgett, 2000; Kreher & Schwartz, 2012).

The syndrome can be diagnosed as a large drop off in performance when comparing against a consistent standardized level tracking back over a number of months. During this time the player has plateaued in performance, became ‘stale’ in training or maladaptation has occurred in training and competition. However, medical science can’t determine the exact causes for an athlete to experience UUPS, yet can only hypothesis a number of events. These variables can consist of:

-

an overload of a mechanical stimulus,

-

psychological stress,

-

family or relationship problems at home,

-

a poor diet and lifestyle choices leading to an inability to recover properly,

-

lack of quality sleeping routine,

-

long distance travelling,

-

a long term injury not fully dealt with or

-

a combination of the variables mentioned above

(Budgett et al., 2000; Johnson & Thiese, 1992).

With regards to rugby players, symptoms to out for

-

if a player is becoming overtraining is a reduction in performance markers in repeated power bouts,

-

not being able to produce significant amounts of force,

-

potentially a reduction in bodyweight and lean muscle mass.

Also, as overtraining symptoms are very individual, changes in personality traits can be picked up on such as a player is constantly

-

in a depressed state,

-

mood swings,

-

poor body language and attitude,

-

low energy levels and

-

complaining of always feeling fatigue

(Stone et al., 1991; Robson, 2003).

Setting up and implementing a batch of monitoring tests can highlight when an athlete is becoming ‘overtrained’ which will prevent any long term implications such as UUPS, illness and injury. Any action plan to reduce fatigue can take place by increasing athletes rest and recovery time and decreasing overall training load and session intensity.

Basic GAS Model

The Window of opportunity

Functional Overreaching

Non-Functional Overreaching

UUPS

Ideal Athletic Development

Reference List:

Bartholomew, J. B., Stults-Kolehmainen, M. A., Elrod, C. C. and Todd, J. S. (2008) Strength gains after resistance training: the effect of stressful, negative life events. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22, 1215-1221.

Bishop, P. A., Jones, E. and Woods, K. A. (2008) Recovery from training: a brief review. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22, 1015-1024.

Budgett, R. (2000) Overtraining and chronic fatigue: the unexplained underperformance syndrome (UPS). International Sports Medicine Journal, 1, 1-9.

Budgett, R., Newsholme, E., Lehmann, M., Sharp, C., Peto, T., Collins, D., Nerurkar, R. and White, P. (2000) Redefining the overtraining syndrome as the unexplained underperformance syndrome. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 34, 67-68.

Coutts, A. J., Reaburn, P., Piva, T. J. and Rowsell, G. J. (2007) Monitoring for overreaching in rugby league players. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 99, 313-324.

Halson, S. L. and Jeukendrup, A. E. (2004) Does overtraining exist? An analysis of overreaching and overtraining research. Sports Medicine, 34, 967-981.

Johnson, M. B. and Thiese, S. M. (1992) A review of overtraining syndrome – recognizing the sign and symptoms. Journal of Athletic Training, 27, 352-354.

Kentta, G. and Hassman, P. (1998) Overtraining and recovery: a conceptual model. Sports Medicine, 26, 1-16.

Kreher, J. B. and Schwartz, J. B. (2012) Overtraining syndrome: a practical guide. Sports Health, 4, 128-138.

Matos, N. F., Winsley, R. J. and Williams, C. A. (2011) Prevalence of non-functional overreaching/overtraining in young English athletes. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 43, 1287-1294.

Meeusen, R., Duclos, M., Gleeson, M., Rietjens, G., Steinacker, J. and Urhausen, A. (2006) Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of the overtraining syndrome. European Journal of Sport Science, 6, 1-14.

Robson, P. J. (2003) Elucidating the unexplained underperformance syndrome in endurance athletes. Sports Medicine, 33, 771-781.

Selye, H. (1950) Stress and the general adaptation syndrome. The British Medical Journal, 1, 1383-1392.

Souza, R. W. A., Aguiar, A. F., Vechetti-Junior, I. J., Piedade, W. P., Campos, G. E. R. and Dal-Pai-Silva, M. (2014) Resistance training with excessive training load and insufficient recovery alters skeletal muscle mass-related protein expression. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28, 2338-2345.

Stone, M. H., Keith, R. E., Kearney, J. T., Fleck, S. J., Wilson, G. D. and Triplett, N. T. (1991) Overtraining: a review of the signs, symptoms and possible causes. Journal of Applied Sport Science Research, 5, 35-50.

Tian, Y., He, Z., Zhao, J., Tao, D., Xu, K., Midgley, A. and McNaughton, L. (2014) An 8-year study of overreaching in 114 elite female Chinese wrestlers. Journal of Athletic Training, 49, 000-000.